When it emerges grayish white from the egg, its webbed feet are already pink. Like its beak, still very short, to allow it to be nourished by the long curved beak of its parents with the milky and extremely nutritious substance that they produce from special glands, during the period of raising their only chick. It is quite precocious and does not stay long in the nest, where the adults take turns caring for it, to go and get food. But even with the appearance of the juvenile plumage, the chick of the Phoenicoprterus roseus remains predominantly white, although the first gray and black feathers also begin to stand out. Black will forever remain the color of all the powerful flight feathers, thanks to which it will be able to complete its long seasonal migrations. The rest of the large body with the long neck will gradually acquire, increasingly marked with age, the spectacular characteristic coloration of the pink flamingo.

The distinctive color, in the adult phase, is declined in the most varied tones and shades, from the most delicate of the plumage to the more decisive, even in some places gaudy, of the wing coverts, depending on the age, the different parts of the body and above all the food that the flamingos feed on. Yes, because the pink and its gradation depend on the diet, in particular on the availability in their diet of small crustaceans such as Artemia salina rich in carotenoids, which are deposited in the feathers coloring them.

Among the six species of flamingos existing in the world, the pink one lives in the Mediterranean, as well as in the rest of Europe, in Africa and in Asia. In Italy, it is estimated that at least 15 thousand individuals are sedentary, thousands more arrive with seasonal migrations and populate the ponds of Sardinia, the salt pans of Trapani and the nearby Egadi, other wetlands also near Marine Protected Areas. Its habitat coincides precisely with the coastal wetlands, where there are shallow and brackish waters.

These are social birds, which gather in colonies of thousands of individuals, especially during the spring nesting periods, when they meet in the chosen areas, not necessarily always the same ones, where they find the best conditions for reproduction, preceded by complex group nuptial displays. They are monogamous and each couple builds its own conical mud nest, where it lays a single egg. And always together, the male and female take care of the incubation and, after hatching, of the raising of the single chick that, after about ten days, leaves the nest to join other peers in large groups looked after by a few adults, allowing the others to move in search of food. The first flights of the chicks begin around two months, while they reach sexual maturity in the second or third year of life, when the pink of the livery becomes more evident.

The long curved beak, fuchsia pink with a black tip, is shaped so that it filters the water through special lamellae that it expels after having retained crustaceans, bivalves, annelids and larvae, small blue-green algae, seeds and plant fragments. It can also use very salty water, such as in salt marshes, since it is equipped like other sea birds with a salt gland, which allows it to expel excess salt from the nose. Another fundamental gland (uropygial) is located above the tail and secretes sebum, in this case also containing beta-carotene, which the animal spreads with its beak on the plumage, after having carefully cleaned and washed it, to restore its impermeability. With this operation, flamingos also revive the pink/reddish color.

At rest, flamingos often stand on one leg, while the other is drawn up against their body. The usefulness of this behavior is not yet understood. But they are migratory birds, which make long and frequent journeys throughout the year, thanks to their powerful wings and a wingspan that in adult males can exceed one and a half meters. And watching them as they slowly take flight or while they are traveling, unmistakable for their color, is an unforgettable spectacle.

Due to the risk of loss of their habitat, flamingos are an internationally protected species by the EU Birds Directive and the Barcelona and Bern Conventions.

They are the oldest plants on the planet. Already 450 million years ago they lived in the seas and oceans up to the depths reached by the sun's rays. And from the aquatic environment began their slow, progressive conquest of the terrestrial environment through the adaptation that would have transformed them into plants, with roots, trunks and branches, leaves. What the plants of the sea did not have and do not have, composed of a non-differentiated body called thallus, which does not flower and does not bear fruit, but which shares with plants the process from which it draws energy and nourishment, chlorophyll photosynthesis.

It is chlorophyll that gives the algae that color green. About 1,500 plant species, mostly Chlorophytes, which can be unicellular, multicellular or colonial. And they live in the sea, near the coast or at fairly shallow depths, to be able to take advantage of sunlight. That light is the vital element that is fundamental for their metabolism. So are water and carbon dioxide that photosynthesis transforms into nutrients, making the algae green like plants capable of autonomously producing the substances they need to live and grow.

This same process brings a great advantage more generally, from an ecological point of view, since the algae – like plants – absorb large quantities of carbon dioxide, releasing, as a waste product of the production of nutrients, oxygen which, in turn, is essential for the life of the sea itself and the animal species that populate it.

Green algae live on reefs and submerged rocks, anchored with rhizoids that resemble plant roots, but also on sandy substrates such as the Club Alga (Dasycladus vermicularis). Some species live in Seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadows, the marine plant with which they share the need for light for photosynthesis, both on long leaves and on rhizomes. Other algae, however, are epiphytes and are found on corals and other algae.

While single-celled algae reproduce simply by replicating, multicellular algae multiply when fragments detach from the original thallus and then grow larger, forming new organisms identical to the one they came from. Some species release spores that, in favorable conditions, divide, forming other cells from which new thalli arise, always identical to the one that produced the spores.

Green algae are rich in vitamins A, B and K, minerals such as iodine and iron and antioxidants, so much so that they are considered a real superfood, also due to the notable presence of omega 3. They therefore have recognized antioxidant properties and are considered useful for the cardiovascular and cerebral systems.

The most common and widespread green algae, at home in the Mediterranean, but also present in other temperate and cold seas, is the so-called Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca) of the Ulvaceae family. It lives and grows, attaching itself with what is called a foot, which is actually a small disk, to rocks and sandy substrates, but also to the shells of marine animals. It looks like a long green leaf and resembles terrestrial lettuce and is also used in cooking, in various parts of the world. In Italy, in Campania, it is the main ingredient of sea zeppoline.

Green algae present in the Mediterranean also include the Acetabularia acetabulum, the Anadyomene stellata, the Bryopsis (Bryopsis plumosa), the green candle (Codium fragile), the green balls (Codium bursa), the Codium coralloides, the Codium vermilaria, the Cladophora prolifera, the Cladophora vagabunda, the Chaetomorpha aerea, the sea club (Dasycladus vermicularis), the Enteromorpha intestinalis, the sea penny (Halimeda tuna), the velvet seaweed (Palmophillum crassum), Pennicillus capitatus), the furcellata algae (Pseudochlorodemsis furcellata), the sea fan algae (Udotea petiolata), the sea lettuce algae (Ulva rigida), the Ulva intestinalis, the Valonia (Valonia macrophysa).

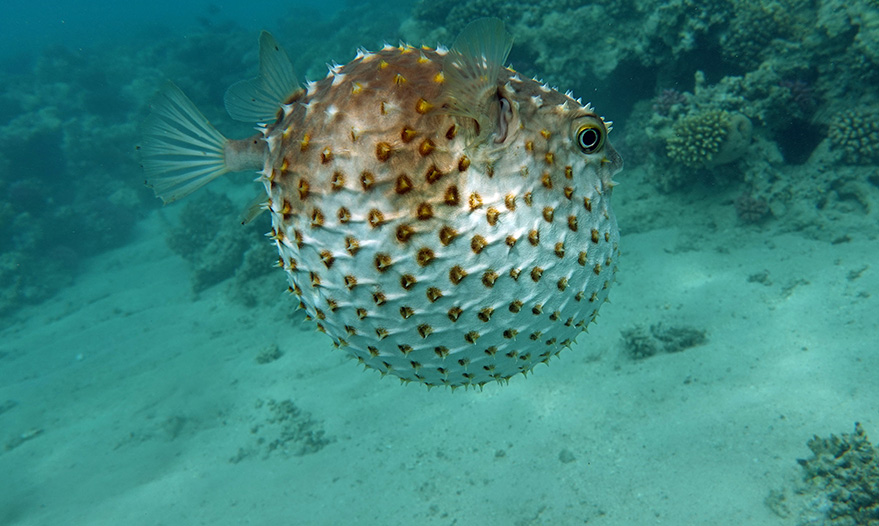

It took ten years, from its first appearance in the eastern Mediterranean, for it to arrive in the Italian sea, in Lampedusa. And since then, it was 2013, it took another twelve years to travel up the Adriatic, until it reached Croatia, where an adult male specimen was just found in the northernmost point among those where the Silvery or Spotted Puffer Fish (Lagocephalus sceleratus) had been reported so far. Another Lessep

sian alien that does not stop its advance to conquer the Mare Nostrum and that is not at all welcome, considering that it is a toxic species, that does not bring any benefit to the ecosystem, on the contrary.

Like the other approximately two hundred species of puffer fish, the “silver” one is also native to the Pacific and Indian oceans, where it lives in coral reefs and along the coasts. And the Lagocephalus sceleratus is linked to the others by the presence of a poisonous substance, tetrodotoxin, from which the name of the Tetraodontidae family comes, which is one hundred times more toxic than cyanide. In fact, it has caused numerous cases of poisoning and even death in the eastern Mediterranean where the inexorable expansion of the puffer, arriving from the Suez Canal, began.

This is an animal that is decidedly armored against any potential predator: a bony fish, with a large head and large eyes, a single dorsal fin, without scales, but with spines on the belly and back, which remain close to the body and are almost unnoticeable when the animal is calm. They rise, ready to cause damage to the opponent, only when the fish swells, with the defensive mode that most identifies members of the entire family: it takes in sea water from its mouth, which it pushes into a diverticulum up to a closed bag in the stomach. When it swells, the spines also come out, making it indigestible and dangerous even for sharks.

The toxic substance is present in the innards, but makes every part of the body poisonous, even after normal cooking. Therefore, the puffer is also dangerous for humans both in contact with any part of the body and if it is ingested, with the exception of a cooking technique developed to make it edible and used by the Japanese, who are the only ones to eat it and also consider it a gastronomic delicacy. In Italy, the consumption of puffer fish has been expressly prohibited since 1992 and fishermen are required, in the event of accidental capture, to immediately isolate it from the rest of the catch.

Another dangerous part of the puffer fish is its mouth. In order to feed on pieces of coral, crustaceans and mollusks, it has very strong teeth that allow it to break and crush shells, shells and coral structures. Therefore, if it thinks it is being attacked, it can also bite humans, causing irreparable damage to their limbs. However, among the puffer fish's prey there are also worms and sponges and in order to extract them from the sand, it causes a strong jet of water that facilitates its capture.

The silver or spotted puffer fish like the one caught in the upper Adriatic, in particular, has an oblong body and is silver in color with black spots on the back.

In order to monitor its expansion, the collaboration of fishermen is essential. In case of capture, they are invited to photograph the specimens and promptly report it to Ispra.

In any case, anyone who spots a puffer fish can report it to

Its common name in several languages including Italian associates it with the Gorgons. And one of them, Euryale, is evoked by the order of the Euryales to which it belongs. But it is certainly not a monster, as the mythological figures with hair formed by snakes were considered. Quite the opposite.

The Gorgon star or Astrospartus mediterraneus is a marine animal of astonishing beauty. A living lace, when at night it completely opens its spectacular tentacles to get food. And it is in that form that the reference  to the Gorgons appears evident. And the origin of its scientific name from aster, star, and spartus, shrub, for the numerous ramifications of its arms. Instead, during the day, when it is not busy feeding, and folds its tentacles, it forms a sort of ball or basket that justifies the name in English of basket star.

to the Gorgons appears evident. And the origin of its scientific name from aster, star, and spartus, shrub, for the numerous ramifications of its arms. Instead, during the day, when it is not busy feeding, and folds its tentacles, it forms a sort of ball or basket that justifies the name in English of basket star.

The Astrospartus lives at depths between 30 and 800 meters in the western Mediterranean and the North Atlantic, along the coasts of Spain and West Africa up to Senegal. Widely distributed off the African coast of the Mediterranean, it is less so around Italy, where, although it is present from the sea of Sicily to those of Tuscany and Sardinia, it is quite rare to meet it. Since it is a photophobic animal, which avoids light, it is active at night and prefers poorly lit and deep sites.

With its light color, which can vary between gray and yellow with pink hues, it stands out against the dark red of the red gorgonian (Paramuricea clavata), also a filter-feeding animal, on which it prefers to settle, but it also does so on the white gorgonian (Eucinella singularis) and on various species of sponges. To attach itself to the animals it hosts, it uses small hooks present at the ends of the numerous branches of its ten, thin tentacles. They all start from the central body, formed by a disk with a maximum diameter of around 8 centimeters, in which the five symmetrically arranged sectors can be distinguished. They are the distinctive element of the Echinoderms, of which the Astrospartus is also a part.

The body has a mouth, to which the tentacles bring food, as they capture it by filtering the plankton present in the water column, but also by wrapping and "imprisoning" small fish and marine animals. The width of the crown of tentacles with all their ramifications, when fully unfolded, can reach 80 centimeters in diameter, thus tenfold the size of the central body and serves to procure as much food as possible. Then, when the need to feed is satisfied, the scenic offshoots are folded one after the other, until they form the basket shape typical of the resting phase of the beautiful sea gorgon.

He never gives them up. And every time he moves to a larger shell, he takes care to prepare an adequate accommodation in the new home also for his faithful traveling companions. And life companions. The only ones with whom he agrees to share the “domestic” space in which he notoriously does not like intrusions, not even from his peers.

It is no coincidence that, together with the recovery shell adapted from time to time to the new measurements of its growing body, the Paguro Bernardo carries with it that nickname of “hermit” borrowed from its solitary existence. The only exceptions are the anemones anchored on its shell, belonging to the species Calliactis parasinica, which for this consolidated symbiosis is naturally associated with the Pagurus bernhardus.

Community life, the result of a long and complex adaptation, has advantages for everyone. For the hermit crab, which always carries them with it, those polyps represent a precious life-saving protection. Sea anemones, in fact, are cnidarians, anthozoans, hexacorals. Cnidarians, as they have stinging cells that, placed on white filaments called acontia, come out as soon as they are attacked by predators. In this way, the anemones defend themselves and also the hermit crab that hosts them. Furthermore, their presence on the shells, favors their camouflage on the seabed, helping the hermit crab to hide more effectively from its attackers.

Even for sea anemones, the advantage of cohabitation is notable. First of all, thanks to the hermit crab that carries them on its shell, they can move around without any effort and with movement they have a greater chance of feeding. And then they can always make use of the leftovers from their host's meals. The host really takes care of them, willingly accepting their presence on the shell in which it is installed. And furthermore, every time it is forced to change it, it takes care to move one by one the anemones it lives with onto the new shell. Bernardo and his anemones are one of the most astonishing examples of mutualistic symbiosis that is established between the inhabitants of the sea depths.

Si era ancora nel dopoguerra, quando lo scarico delle acque di sentina di qualche nave proveniente dall’Oceano Atlantico affidò al Mediterraneo una nuova specie di granchio che nessuno conosceva. E di cui ancora a lungo si sarebbe ignorata la presenza nella laguna di Grado, in Alto Adriatico, dove era comparso per la prima volta nel lontano 1949. Nulla lasciava presagire allora e neppure nei decenni seguenti che il Granchio blu, nome scientifico Callinectes sapidus, settant’anni dopo si sarebbe rivelato un vero e proprio flagello, capace di stravolgere interi ecosistemi e di annientare una delle specie animali di cui è predatore, la preziosa vongola dalla quale dipende l’economia di tante aree della costa adriatica.

Dopo tanti anni di silenziosa, anonima presenza nelle lagune dell’Italia nord-orientale, riconosciuto solo nel 1993 ma ancora apparentemente innocuo, il granchio nuotatore, come pure viene chiamato, ha iniziato a moltiplicarsi in modo esponenziale a partire dal 2010, dando inizio a una diffusione velocissima, che lo vede ora stanziale in quasi ogni parte d’Italia, anche se i danni maggiori li sta facendo nell’Adriatico tra Friuli, Veneto ed Emilia-Romagna. Una proliferazione incontrollabile da ricondurre all’innalzamento delle temperature a terra e a mare, che hanno portato al livello massimo la prolificità della specie. Originaria dell’Oceano Atlantico occidentale, dove è presente dalla costa statunitense fino all’Argentina, e in particolare nel Golfo del Messico. Orami insediata, tuttavia, oltre che nel Mediterraneo, anche nel Mar Baltico, nel Mar Nero, nel Mare del Nord e nel Mar del Giappone. Un areale immenso, che si incrementa a vista d’occhio.

Crostaceo della famiglia Portunidae, il granchio blu si identifica anche nel nome con la sua colorazione più vivace e appariscente, il blu di alcune parti delle zampe e delle chele, nelle sole parti laterali per tutti gli individui e per i maschi anche nelle punte, che invece nelle femmine sono di uno squillante rosso aranciato. Altro elemento di dimorfismo sessuale è la forma dell’addome: nel maschio somiglia a una T, nelle femmine adulte è ovale rotondeggiante e triangolare nelle giovani. Come tutti decapodi, anche il granchio blu ha cinque paia di zampe di cui l’ultimo paio posto anteriormente, più lungo degli altri quattro, è trasformato in chele.

Il corpo del maschio raggiunge i venticinque centimetri di larghezza, quello della femmina, più piccolo, i venti. E la larghezza è il doppio della lunghezza. Il carapace presenta sia nella parte anteriore che in quella laterale nove paia di denti, di cui il più posteriore è allungato a formare una spina. Due denti triangolari sono pure sulla fronte.

Prolifico e capace di vivere nelle più varie condizioni

Il granchio blu vive in media tre o quattro anni, al massimo può raggiungere gli otto. Ha una grande capacità di adattamento sia alle temperature - dai 5 ai 35 gradi - sia al grado di salinità delle acque: da quelle più dolci degli estuari dei fiumi, a quelle più saline delle lagune e del mare, fino ad acque fortemente salate. I maschi preferiscono acque meno salate, le femmine più salate come i neonati. I granchi popolano habitat sabbiosi e fangosi, ma nella fase giovanile crescono al sicuro nelle praterie di fanerogame marine. La capacità di adattamento si riscontra anche nell’alimentazione, visto che è un animale onnivoro, che si nutre di alghe, di crostacei, anellidi, piccoli pesci e perfino di insetti. Ma apprezza particolarmente i bivalvi, tra cui cozze, ostriche e vongole. Nei casi di forte affollamento e di riduzione di altre prede, è normale il cannibalismo di esemplari adulti e più grandi rispetto ai piccoli.

La specie è straordinariamente prolifica. Anche se le femmine si accoppiano solo una volta nella vita, dopo l’ultima muta, mentre i maschi più volte. Ogni femmina depone dalle settecentomila agli otto milioni di uova e lo fa spostandosi in tratti di mare con maggior livello di salinità, perché è la condizione ideale per le larve che nascono dopo il periodo di incubazione della durata tra i quattordici e i diciassette giorni.

La grande capacità riproduttiva del granchio blu, unitamente alla varietà di condizioni in cui gli è possibile vivere anche nel Mediterraneo, hanno fatto sì che questo granchio alieno riuscisse a insediarsi stabilmente in aree costiere sempre più ampie e con popolazioni sempre più numerose, che i predatori naturali – pesci, tartarughe marine e uccelli – non riescono a contenere. E vale anche per il predatore principale, ovvero l’uomo, tanto che ormai gli eserti concordano sull’impossibilità di eradicare ormai il granchio blu dal nostro mare.

Eppure, si tratta di una specie che rappresenta un problema sempre più serio per l’impatto estremamente distruttivo che ha sull’ambiente. Dove si moltiplica il granchio arriva il deserto, vista la voracità con cui annienta le specie di cui si nutre, colpendo in particolare gli allevamenti di vongole in Adriatico. Negli ultimi anni, i granchi hanno determinato una riduzione di oltre il 70 per cento della produzione di vongole nel Delta del Po, infliggendo un colpo durissimo all’intero comparto economico e all’occupazione che vi ruota intorno.

Per cercare di contrastare l’emergenza granchio blu sono stati previsti investimenti specifici, mirati a sostenere gli allevatori/pescatori di vongole e a finanziare ricerche sui granchi e azioni specifiche di contrasto. Il tentativo di contenere la moltiplicazione dei crostacei, trasformando essi stessi in un prodotto commerciale per il consumo umano, non ha avuto i risultati sperati. Se, infatti, il granchio è considerato una leccornia nei Paesi atlantici di cui è originario, in Italia e in Europa non ha avuto finora altrettanto successo. Per cui la perdita delle produzioni di vongole non è stata compensata dalla commercializzazione dei granchi, come si auspicava.

Tra le ipotesi di contrasto alle quali si continua a lavorare, vi è la ricerca di predatori naturali in grado di contenere le popolazioni in crescita. E le notizie più recenti segnalano con interesse la possibilità che il polpo comune (Octopus vulgaris) possa diventare un efficace nemico, in grado di ripristinare un minimo di equilibrio lì dove il crostaceo blu lo ha compromesso. Riuscirà a portare a buon fine l’impresa, il campione dai lunghi tentacoli?

These are the numbers that can be read on the boxes in fishmongers and on all the packaging of fish products. Established by the FAO the United Nations organization for food and agriculture, to indicate the different fishing areas in the oceans and inland seas.

Numbers that are not always followed by the name or an explanatory image as required, so they are often difficult to understand for buyers. And instead of the purpose of that numerical indication is precisely to guarantee maximum information and transparency on the origin of fish, crustaceans and molluscs intended for consumption, to allow the consumer to make an informed choice.

The FAO codes are composed, in order, of numbers that indicate the Zones, or the parts of the oceans identified as the main references and, within them, other numbers identify the Subzones and, as a further specification, the Divisions. The FAO Zone that most directly concerns Italy is number 37, which identifies the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. This includes three subzones, each of which is divided into some divisions.

Subarea 37.1 identifies the western Mediterranean Sea, from Gibraltar to the western coast of the Peninsula. Within it, there are division: 37.1.1 for the Balearic Sea; division 37.1.2 for the Gulf of Lion; division 37.1.3 for the Sardinian Sea, including the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Subarea 37.2 concerns the central Mediterranean Sea, from the eastern coast of Italy to the Balkans and in North Africa Tunisia and Libya. It includes Division 37.2.1 of the Adriatic Sea and Division 37.2.2 of the Ionian Sea.

Subarea 37.3 is the eastern Mediterranean Sea with Division 37.3.1 for the Aegean Sea and Division 37.3.2 for the Levantine Sea, which reaches the coasts of Greece, Türkiye, Lebanon, Israel and Egypt.

Zone 37.4 identifies the Black Sea.

THE OTHER FAO ZONES: Zone 18 Arctic Sea; Zone 21 Northwest Atlantic; Zone 27 Northeast Atlantic; Zone 31 West Central Atlantic; Zone 34 East Central Atlantic; Zone 41 Southwest Atlantic; Zone 47 Southeast Atlantic; Zone 48 Atlantic, Antarctic; Zone 51 Western Indian Ocean; Zone 57 Eastern Indian Ocean; Zone 58 Antarctic and South Indian Ocean; Zone 61 Northwest Pacific; Zone 67 Northeast Pacific; Zone 71 West Central Pacific; Zone 77 East Central Pacific; Zone 81 Southwest Pacific; Zone 87 Southeast Pacific; Zone 88 Antarctic Pacific.

European indications

According to the provisions of EC Regulation No. 1379/2013, in particular Article 35, fish placed on the market must bear, mandatorily, the commercial name, in accordance with the official list of fish species drawn up by each country, and the corresponding scientific name; the indication of fishing gear and methods of capture and the FAO fishing zone, to recognize the product and its origin, which also concerns the seasonality of the fish product.

In Sardegna, la pianta del mare è diventata nutrimento delle piante a terra. Si chiama “Posidonia Garden” ed è un progetto innovativo ed efficace di trasformazione della Posidonia secca spiaggiata in composti per orti e giardini.

For decades, the monk seal (Monachus monachus) has been practically a ghost, the protagonist of a few sightings in the open sea so rare as to deserve official announcements and prominent newspaper headlines.

The element that most distinguishes it even to the least expert eye, so much so that it is included in its common name, is a tuft of curved feathers on the head that is part of the male's nuptial plumage.

The flight is long and demanding, the search frantic. Every day, when the color of the night gives way to the first light of dawn, until the setting sun floods the surface of the sea with gold.

Very delicate ribbons, arranged in a spiral, form transparent yellowish-white skeins that stand out on the dark rock, in sheltered and shady spots. They are deposited on the seabed by an animal with an unmistakable mantle, which also stands out among all the other creatures present in the marine environment. Flat, oval in shape, a milk-coloured body crawls slowly with numerous brown spots of various shapes and sizes, outlined by a darker edge. The common name by which this strange specimen is known, Sea Cow (Peltodoris atromaculata), is not surprising. A gastropod mollusc of the order Nudibranchs, completely without a shell, classified in the suborder Doridina because of the sensory appendages it displays on its head, called rhinophores, white and retractable. Another peculiarity is the gills, between six and nine and also retractable, which appear as a whitish tuft, located on the rear part of the body.

Those ribbons left on the bottom contain the eggs of the sea cow: very small, white or yellow in color, they are laid in various stages, during the summer period by the adults, who are hermaphrodites, both male and female at the same time. From the eggs, larvae are born, equipped with a tiny shell, which become part of the plankton, until, having escaped the many predators, they reach the right size to return to the bottom and begin life as adults, now without their shell.

On average, between five and seven centimeters long, the cows, also known as Dotted Sea Slug, can reach twelve centimeters. As they grow, the size of their spots also increases in proportion, and their shape is a characteristic element of each individual. During the egg-laying phase, which lasts for several days, the animal loses weight and becomes smaller. This, after all, is the culminating moment of its life cycle, which lasts a year and ends just a few weeks after reproduction.

Widespread throughout the Mediterranean, the Sea Cow lives between 5 and 50 meters deep, mainly on coralligenous and rocky substrates, but also in Posidonia meadows. Wherever its prey, which are sponges, are found. In fact, it spends most of its life on them, scraping their porous surface with its designated organ, the radula. The nudibranch is fond of only two species of sponges, Petrosia ficiformis and Haliclona fulva.

A great work destined to revolutionize navigation, international trade and the world economy.

All this was well known to those who, investing considerable resources, wanted to build the Suez Canal, inaugurated in 1869. Not as much attention and consideration had probably been reserved for the environmental changes that that intervention could have brought about in the short and, even more so, in the long term. Certainly, Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, at the head of the French company that had built the canal connecting the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, would never have imagined that so many decades later, in 2010, his surname would give rise to an adjective, “Lessepsian”, coined by the great Romanian zoologist Francis Dov Por. An adjective that has since then been used to define all organisms, mostly animals, but also plants, that have moved from the tropical environment of the Red Sea and also the Indian and Pacific Oceans to the Mediterranean and have settled there permanently.

They are the vast majority of the so-called “alien” organisms, since the number of species that arrived from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar is much lower. Moreover, animals and plants that followed the reverse path from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea are defined as “antilessepsians”, but in rather small numbers.

The first aliens were passively introduced into the new Mediterranean area with the bilge water of ships or attached to the keels. Only later did the actual migration begin, favored over time by some changes linked to the long-term effects of the environmental impact of the canal and related works. At the beginning, in fact, the movement of species from the Red Sea was blocked both by the different temperatures of the Mediterranean and by the very high salinity of the Bitter Lakes, an integral part of the canal. In those lakes, the species that ended up there did not survive. It was, therefore, an extremely effective natural barrier. But then the external connection determined the introduction of fresh water into those basins, which progressively reduced the initial salinity by half, making the Bitter Lakes a viable connection also for the native species of the Red Sea, as well as for ships. The construction of the second Aswan dam in 1971 and the restyling with the expansion of the canal in 2015 created other conditions favorable to migration.

Between the end of the 19th century and the end of the 20th century, it was observed that most alien species, all of tropical origin, once they entered the Mediterranean, remained in its southernmost and easternmost part, finding habitats more compatible with those of origin. The rise in sea temperature, which has accelerated in the last thirty years, with an increase of about one degree, has made an expansion towards the west possible. And, in addition, that towards the north has been added, which is also affecting native species.

The story of Halophila stipulacea is exemplary: the tropical marine plant was first spotted in the Mediterranean in 1894. Since then, it had remained in the eastern part of the basin for a long time, before starting to spread westward, until it appeared in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where it reached France, and in the Adriatic. A study by the University of Salento, published in 2023 in the scientific journal “Mediterranean Marine Science”, revealed that the plant has formed large meadows off the coast of Salento, so much so that researchers have launched an appeal to assist in the monitoring activities necessary to verify the transformations in the marine environment, induced by such a massive presence of the alien.

The same phenomenon has affected, or rather is still affecting, many of the animal species from the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Among the many, the dark rabbitfish (Siganus luridus), which is very widespread in the eastern Mediterranean, where its strong environmental impact has already been experienced. In fact, as a herbivore that feeds on brown algae, it has created a lot of damage where its presence is massive. In Italy it was sighted in 2003 for the first time and since then, although sporadic, other sightings have followed. The same can be said for the striped rabbitfish (Siganus rivulatus), which appeared in Italian seas for the first time in 2015.

Its bright orange color stands out unmistakably on the walls of submerged caves or on rocks populated by corals, gorgonians and other animals characteristic of the coralligenous. What creates that extraordinary special effect in the depths of the Mediterranean and in some areas of the eastern Atlantic is not the single specimen of Parazoanthus axinellae, commonly known as yellow cluster anemone, given its tiny size, but the extension of the colonies, which group together thousands and thousands of polyps, fixed to the substrate with a soft and unique stolon.

They are really small, the polyps, just five millimeters in diameter and about twenty in height. Each polyp has a basal part and an erect part that is retractable. The entire body is equipped with stinging cells (cnidocysts) that place the anemone among the Cnidaria or also Coelenterates, because they have a gastric cavity called coelenteron. Belonging to the class of Anthozoa, being a polyp, the anemone is a hexacoral, because it has smooth, threadlike tentacles in number between 24 and 36, therefore multiples of six, arranged in two rows around the mouth and equipped, more than the other parts of the body, with stinging cells. Thanks to the tentacles, the polyps capture the microplankton on which the animal feeds. And precisely to have food available, the species settles in places where the movement of the currents is strong. Another requirement is low light, not by chance Parazoanthus is present in marine cavities or in any case on rocky walls in the shade. The depth varies from 5 to 50 meters mostly, but colonies are found up to 200 meters. Where it encounters favorable conditions, the species expands like a carpet even on very large surfaces. The colonies can merge or split.

The groups include male and female specimens, which reproduce in spring, with the laying of eggs in March. At the end of autumn, planktonic larvae are released from the eggs and are transported by the current to create new colonies.

If they prefer hard and rocky substrate, yellow cluster anemone can also settle on other animals. And their scientific name already reveals a symbiosis with some sponges of the Axinellidae family – Axinella darmicornis and Axinella verrucosa – which are also filter-feeding animals and have the same yellow color. In addition to sponges, anemones also settle on other species of sponges (Petrosia, Agelas and Sarcotragus), on tunicates of the genus Microcosmus and on the yellow gorgonians Eucinella cavolinii and on the white Eucinella verrucosa.

If it were not always on the move, while it explores the shoreline with its long beak in search of food, its livery and size would make it impossible to distinguish it in the expanse of sand.

When you put it to your ear, you can hear the sea breathing. The god Triton always carried it with him, playing it to calm the stormy sea and to announce the arrival of his father Poseidon, the god of the sea. The large shell was precious to every sailor, who used it to launch his call to signal the position of the vessel in the fog or to announce the arrival in port. That unmistakable sound also resounded in the countryside, to call the flocks and accompany the special moments of the communities. For millennia, the sea trumpet has been a tool for communication, alarm and even defense against attacks by enemy ships approaching the coast. All possible thanks to a shell, the largest in the Mediterranean after the noble pen shell and among the largest in the world, with a tapered conical shape and bright colors, from white to brown, under the marine encrustations. Inside, an enormous mollusc of about sixty centimetres, which bears the name of the half-man, half-fish god: Giant Triton, Charonia tritonis for science.

For tens of millions of years on the planet, fossils testify to its presence in all seas as other molluscs of the same Charoniidae family, with very similar characteristics that sometimes make them difficult to distinguish. It lives in the oceans and in the Mediterranean, from the east to the Adriatic, to the Sicilian Sea up to the central Tyrrhenian Sea, at a depth between twenty and forty meters. And it prefers rocky or detritus seabeds. Where it finds in abundance the invertebrates on which it feeds such as starfish, sea cucumbers and bivalves.

It mostly devours them whole, even when they are large, and digests them, even the hard parts, thanks to acid secretions produced by the salivary glands. The giant triton is also able to produce saliva that can paralyze its prey, in order to feed on it.

This also allows it to eat the large crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), which live in the Pacific and Indian oceans. Although their rays are covered with spines for protection, they are useless against the giant triton, their only predator. As such, it is considered essential for the defense of the coral reef, which in turn is prey to the crown-of-thorns starfish, which can feed on corals, thanks to powerful digestive enzymes. It is estimated that a single starfish can destroy six square meters of reef a year and the proliferation of crown-of-thorns is seriously endangering corals in various parts of the planet.

For its part, the giant triton has become quite rare in the Mediterranean, where sightings are very few. The population of the mollusc has been drastically decimated by the intensive fishing to which it has been subjected even in recent times both because it is edible and to use its precious shell, no longer as a foghorn or musical instrument, but for collecting purposes.

The giant triton is a species protected by the Bern and Barcelona Conventions, so fishing is prohibited.

It is a plant species that has lived in the sea for over one hundred million years, so it is not an alga. And although its name refers to the ocean, it is widespread only in the Mediterranean, where it is present everywhere in the coastal strip.

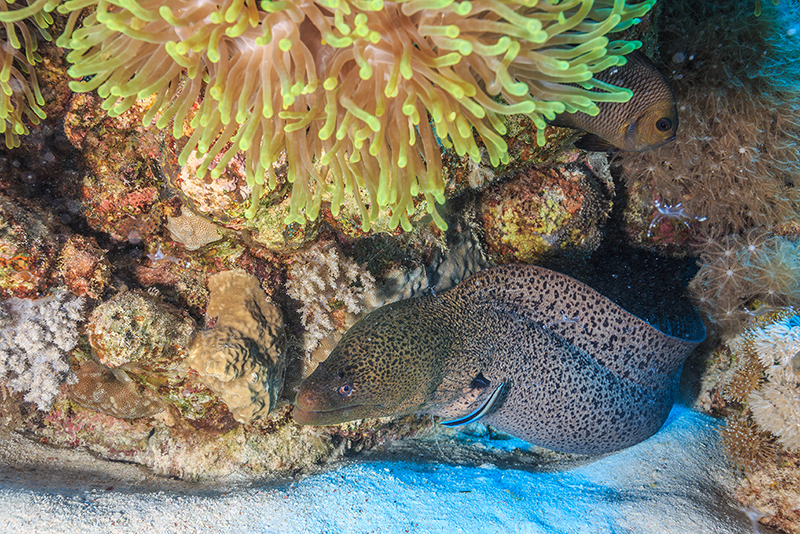

It was 1980 when it was spotted in the waters of Israel, for the first time in the Mediterranean. And since then it has been a slow but progressive expansion towards the west, especially favored in recent years by the increase in sea temperatures, which is particularly affecting the Mediterranean.

A sea that has always hosted fish of the Murenidae family, of which the most widespread representative remains Muraena helena, a close relative of the alien Enchelycore anatina, the official name that identifies the Eastern Moray eel, also known as the “tiger moray eel”. A name, the latter, linked to the bright colors that characterize it, from yellow to orange, to brown, with streaks that can recall the coat of the large terrestrial feline.

From that first report, thirty years passed before we heard about the presence of the snake-like “tiger” in the upper Adriatic, in Croatia. And more than another decade for the first Italian sighting, on the Tremiti Islands, where it made its appearance, at least officially, in 2024, although there is no lack of evidence of previous encounters with the brightly colored moray eel, very different from its local relative with a much more sober brown-blackish color.

The alien moray eel has its reference area in the western Atlantic, where it is present in the sea of the archipelagos of the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Azores and Madeira. The adult male of the species can reach one and a half meters in length and its teeth are transparent. Apart from its color, it has a behavior common to other members of the Murenidae family: it is carnivorous, preys mainly at night and feeds on fish, crustaceans and molluscs, starting with octopuses, which also live in rocky ravines and are one of its favorite prey. The alien moray eel also lives on rocky seabeds and uses cavities and cracks in the rock as dens. And if at tropical latitudes it inhabits coral reefs, in the Mediterranean it is settled in coralligenous areas.

Serpent-like body, devoid of scales, moray eels lack pectoral and ventral fins, but the dorsal and anal fins extend along the entire length of the body, from head to tail. They are equipped with predatory teeth, with long and pointed teeth, which leave no escape to the prey captured without moving from the den, with a lightning-fast and implacable snap.

The original distribution area was already very wide: from the Sea of Japan to Australia, from Polynesia to Southeast Asia, practically the entire tropical and subtropical Pacific and the Red Sea.

Then, about thirty years ago, some specimens escaped from an aquarium in Florida and ended up in the Atlantic. In just a few years, the lionfish (Pterois miles and Pterois volitans) became a household name throughout the Caribbean Sea, with serious consequences for the balance of local ecosystems. But the typical behavior of young fish, who leave their birth sea early to settle elsewhere, also brought some lionfish to the Suez Canal, and from there, their passage to the Mediterranean encountered no obstacles. Thus, since the second decade of this century, they have officially entered the list of “aliens” in the Mediterranean.

Specimens of the genus Pterois, belonging to the two species that have only recently been recognized as distinct (miles and volitans), have begun to take possession of the easternmost waters, between Lebanon, Syria and Turkey, then Cyprus. In that area since 2013, sightings have become increasingly frequent, not only of single specimens, but even of schools, which is indicative of a significant presence, considering that it is a fish with a usually solitary behavior, which rarely aggregates. And for some years, from the eastern Mediterranean there has been a progressive shift towards the west, certainly favored by the increase in temperatures that is being recorded throughout the basin, being a tropical species.

The seas of the Peninsula have not been excluded from this expansion. The first sightings of Pterois date back to 2016, in south-eastern Sicily. Then, other specimens were identified, always solitary, in Sardinia and again in Sicily. With an increase between 2020 and 2022. In the summer of 2023 a scorpion fish was caught in Le Castella, Calabria, by professional fishermen at about 24 meters deep and on June 25 another was photographed at 12 meters, again in Calabria, in Marina di Gioiosa Ionica, by an underwater photographer who promptly reported the alien presence. And in 2024 another sighting was made known in the sea of Puglia. All valuable contributions also for the research groups that study "alien" species and their expansion in the Mediterranean.

Subject, among other things, of a study conducted by the Dutch University of Wageningen and published in the scientific journal “NeoBiota”, which explains how the rapid spread in the Mediterranean represents a danger for the ecosystems here as has already happened in the Caribbean Sea. In consideration of this recognized danger for the ecological balances of our sea, research projects are underway, which include monitoring the spread of that and other alien species, also using the contribution of the many frequenters of the sea, non-scientists, through Citizen Science.

They have a small head, but a large mouth and protruding eyes surmounted by two growths like those found around their chin and used to confuse them with corals, which like them live in rocky habitats. Pterois are mimetic fish, which also use their splendid brown and white striped livery for this purpose, a characteristic alternation of colors also on the fins, which contribute to the recognized beauty of the animal during movement. But the fins also contain the peculiarity that makes scorpion fish dangerous for humans too. On the dorsal fin there are thirteen hollow spines and three more are present on the anal fin: all serve to inoculate poison into enemies from which the Pterois feel attacked. . The spines are connected to a venom gland, from which they “feed” the neurotoxin that remains active for up to 48 hours after the death of the scorpion fish. It is also a dangerous poison for humans that, in the event of a sting, causes great pain and poisoning that can be very serious and that, in some rare cases, has even proved fatal. Therefore, you must be very careful in the event of an encounter with a Pterois and avoid any close contact, even if it is an animal that tends to hide and blend in with the surrounding environment, attacking only when it feels in danger.

The genus Pterois includes ten different species, all tropical, which, despite having great adaptability, live in rocky habitats and coral reefs, usually at low depths, up to 150 meters at most. The Pterois is a nocturnal predator, which feeds on small fish, crustaceans and molluscs. Being very voracious, its massive presence has proven to be extremely destructive outside its original range, where, instead, it plays a valuable role in the food chain and in maintaining the balance of the different populations of sea inhabitants.

Careful to remove the poisonous spines, its meat is edible and therefore, in order to contain its proliferation, it is fished and marketed in the Caribbean Sea, but also in Turkey and Cyprus. Great attention is paid to research on its neurotoxin, for possible applications in the field of medicine.

A large protective umbrella and food, always and conveniently available.

It is the large jellyfish of the Mediterranean that ensure these benefits to some species of fish with which they have created a symbiotic relationship and from which they also benefit. Very different marine creatures, such as the astonishing Mediterranean Cassiopeia (Cotylorhiza tuberculata) and the horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus), protagonists of one of the most characteristic examples of symbiosis offered by our sea. The jellyfish with the fascinating mythological name has a decidedly strange appearance and is so characteristic that it is unmistakable: observed from above, the umbrella appears like a large fried egg, with a bright yellow swelling surrounded by a white disk and is in fact also known as the "fried egg jellyfish".

The jellyfish with the fascinating mythological name has a decidedly strange appearance and is so characteristic that it is unmistakable: observed from above, the umbrella appears like a large fried egg, with a bright yellow swelling surrounded by a white disk and is in fact also known as the "fried egg jellyfish".

The edge of the umbrella can take on a greenish color, indicative of the presence of tiny zooxanthellae algae, with which it also maintains a symbiotic relationship, like many other marine animals. Under the umbrella, which can reach thirty centimeters in diameter, like its other sisters belonging to the order of Rhizostomeae, it has arms with numerous ramifications in which the oral orifices through which it feeds are located. The arms, which end with small blue/purple buttons, are therefore not tentacles as in other species of jellyfish and, in the case of Cassiopeia, they do not have stinging cells, so they are also harmless to humans.

Among those filaments, small schools of young horse mackerel find a safe refuge from predators, which also take advantage of the protective jellyfish to easily stock up on food. The jellyfish, in turn, uses the small fish that follow to get rid of parasites and unwelcome guests.

The horse mackerel or suro belongs to the Carangidae family, therefore it is a pelagic bony fish, also present in the Mediterranean, as well as in the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea. It lives mainly at great depths, up to a thousand meters, but it can also be found at lower depths, closer to the coast, in shady areas. The schools face seasonal migrations to find constant temperatures. The single specimen has an average length of about thirty centimeters, an iridescent green color, silver sides with a black spot on the operculum and one on the pectoral axil with gray dorsal fins, whitish anal and ventral fins, gray-green pectoral and ventral fins.

The symbiosis of juvenile horse mackerel, which are immune to the stinging liquid of jellyfish, does not only concern Cassiopeia, but also the other large jellyfish of the Mediterranean, the sea lung (Rhizostoma pulmo). The same is true for the juveniles of another carangid, the amberjack (Seriola dumerili), and fish of the Sparidae family such as salema (Sarpa salpa) and bogue (Boops boops).

«Garantire uno stato di conservazione favorevole per i mammiferi marini ed il loro habitat proteggendoli dall’impatto negativo delle attività umane», è con questa finalità che dalla fine del secolo scorso tre Paesi confinanti del Mediterraneo settentrionale - Italia, Francia e Principato di Monaco - hanno unito le forze per creare la più grande area marina protetta del Mediterraneo, interamente dedicata ai mammiferi marini che la frequentano, numerosi sia per il numero delle specie interessate che per il numero degli esemplari.

Uno dei centri mondiali dello studio dei cambiamenti climatici a livello globale e del loro impatto sugli ambienti marini è il Golfo di Napoli, in virtù delle particolari caratteristiche geologiche di alcune sue aree.

That vivid color, unmistakable and unique with its intensity it’s impossible not to notice. And it’s certainly the first characteristic of the species to be noticed.

Già Plinio il Vecchio nella sua Naturalis historia citava la salamoia di menole, usata a scopo terapeutico mescolata al miele, per la cura di ulcere nella bocca.

Viene utilizzato pesce azzurro, quindi la sarda, l’acciuga, lo sgombro e l’alaccia (Sardinella aurita), della stessa famiglia della sardina, rispetto alla quale è più grande.

Ė un modo antico e gustoso di consumare pesci poveri e con scarso valore commerciale da parte dei pescatori di Porto Cesareo, nelle pause delle lunghe battute di pesca, lontano da casa.

In the wild and sheltered rocky ravines of the islet of Vivara, they can nest undisturbed and contribute to the survival of their species, which is still in danger.

Ė del 22 novembre 2024 la pubblicazione sulla prestigiosa rivista scientifica “Science” di uno studio che ha accertato che gli habitat in cui vivono cetacei nei vari mari del mondo corrispondono al 92 per cento alle rotte marittime più utilizzate.

L’Accordo sulla conservazione dei cetacei del Mar Nero, del Mar Mediterraneo e dell’Area atlantica attigua a ovest dello Stretto di Gibilterra, noto più semplicemente come ACCOBAMS, firmato il 24 novembre 1996 a Monaco e operativo dal 1° giugno 2001, è dedicato alla conservazione e tutela delle 28 specie di cetacei che si muovono nelle acque oggetto dell’intesa e vincola in tal senso i 24 Stati firmatari, Italia compresa.

For centuries it has been the distinctive element of the Christmas Eve dinner of the inhabitants of Cetara.

Pescare in maniera sostenibile significa utilizzare le risorse in modo da assicurarne la conservazione e, dunque, la possibilità di uno sfruttamento futuro, garantendo nel tempo il lavoro dei pescatori, senza compromettere l'ambiente e valorizzando al meglio la capacità delle risorse di riprodursi e rinnovarsi.

Brown Algae

There are about fifty species. Present in every sea, but especially in the Mediterranean, the Pacific and the Indian Oceans. These are the brown algae of the genus Cystoseira, creators of a habitat fundamental for biodiversity in rocky coastal environments, where they proliferate at low depths, because they need light for chlorophyll photosynthesis. The color that distinguishes them is linked, as for all brown algae, to Fucoxanthin: the different gradation and intensity of the brown color depend on the quantity of pigment present in the plant. Which with its bushy development, forms underwater, on the rocky substrate, real forests, extending over large surfaces.

The submerged forests of Cystoseira represent an ecosystem where the most varied species of marine animals find favorable living conditions, including many fish that find refuge there and raise their young. But the extensions of Cystoseira guarantee numerous other benefits where they are still present. In fact, they perform a fundamental function of mitigating the effects of wave motion to protect the coasts from erosion. Furthermore, they produce oxygen and capture significant quantities of CO2. In short, they play a role similar to that of Posidonia oceanica, very precious for the life and health of the sea.

And yet, forests are in decline almost everywhere, including the Mediterranean, due to the effects of anthropization: pollution, urbanization, climate change and the spread of alien species in the Mediterranean. With a serious loss of biodiversity and with consequences linked to the lower production of oxygen and specular lower reduction of carbon dioxide.

It is in consideration of the risk that ecosystems linked to macroalgal forests run that a series of experimental interventions are underway for their monitoring and, above all, for their replanting in some Italian Marine Protected Areas.

Since 2020, a project has been underway in the Tuscan MPA of Secche della Meloria, where the Cystoseira forests have suffered a strong reduction. In an attempt to reverse the current trend, a complex replanting operation has begun, taking thalli (this is what the “bodies” of the algae are called) from the Capraia MPA to transplant them in the northern part of zone A of Meloria. A monitoring action followed, in order to verify the state of health and growth of the transplanted algae. The checks have not revealed any failures, but a good state of the algae transferred elsewhere, which are growing regularly, with the prospect, as soon as they are able to reproduce, of progressively enlarging the colonized area, restoring the lost forest.

Another restoration experiment is underway with the Life REEForest project in the two Marine Protected Areas of the Cilento Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Park, in Santa Maria di Castellabate and in Baia degli Infreschi and della Masseta, in the Marine Protected Area of Bergeggi in Liguria and in the Sardinian Marine Protected Area of the Sinis Mal di Ventre Peninsula, in addition to the MPA of the Greek island of Giaros. With the monitoring of ISPRA, working groups have provided for the reintroduction of thousands of Cystoseira thalli of the crinitophylla and corniculata species. An experimental intervention, which is producing good results in the field, aimed at developing valid guidelines for operating in other areas as well and at raising public awareness of the decline of forests and their value. An action that is part of the European active restoration policies and that is connected to the forest monitoring plan within the United Nations Decade 2021/2030 on ecosystem restoration.

A close relative of gorgonians, with which it shares numerous characteristics as an octocoral and alcyonaceous anthozoan cnidarian,

They are anchored to the rock, on the hard seabed that represents their referencehabitat, at the most diverse depths.

There are plants, such as red algae. And there are animals, such as bryozoans, annelids and anthozoans. Many different species, all benthic and with another common characteristic: the ability to build calcium carbonate structures on the seabed. Mostly hard, made of rock. But also mobile, made of sand and debris. At variable depths, between 25 and 150 meters and even more. With a progressive prevalence of animals, in relation to the reduction in brightness that gradually excludes plants due to their need for light, essential for chlorophyll photosynthesis.

And the affirmation, even among animals, of shade-loving species, which can live with very little light, if not in the dark. All together they are bioconstructor organisms and contribute to the creation of the coralligenous, in fact the equivalent in the Mediterranean and in temperate seas of the coral reefs characteristic of tropical seas. A habitat that, although not recognized as a priority at European level, has an extraordinary value for the very high biodiversity that accompanies it and for its essential contribution to the life of the numerous marine ecosystems that are connected to it and, in general, to the health of the sea. Reason why the coralligenous is considered worthy of special protection, as occurs in the Marine Protected Areas.

The main action in the construction of the coralligenous is carried out by calcareous algae, which produce encrustations on the substrate on which they live. When they die, the thalli (i.e. the “bodies” of the algae) consolidate and overlap in layers, forming over time the calcareous structures to whose growth the skeletons of the animal bioconstructors also contribute. These calcareous buildings, which are in slow and constant growth, create favorable conditions for the settlement of other species, both plant and animal. Among these, also some biodestructors, such as sponges and perforating bivalves or some molluscs, which make space by dissolving parts of the structure and modeling it to form the cavities they need to live.

The various layers of coralligenous correspond to conditions that are useful for the life of the different species that populate it. In the upper layers we can distinguish living algae, but above all erect organisms such as gorgonians (which are anthozoans) with their spectacular shapes and magnificent colors, corals, especially red coral, and madrepores. The cavities dug by biodestructors also serve as a refuge for cephalopods and fish. Among the functions of the coralligenous, in fact, there is also that of a nursery for the young of many marine creatures, which have the possibility of becoming adults and even reproducing there.

The coralligenous plays a valuable and important role in the carbon cycle, therefore from an ecological point of view. And its health is indicative of the overall health of the sea, because its delicate balances are affected and can be put at risk by various forms of environmental degradation: eutrophication which reduces the transparency of the water, affecting the photosynthesis of algae; anchoring which mechanically destroys parts of the structures, killing their inhabitants; the increase in sea temperature, which upsets the living conditions of animals and plants. The phenomenon of sea acidification, then, has a heavy effect both on the calcareous organisms that form the coralligenous and on the already existing and consolidated structures. All themes and problems at the center of attention of the research world, which is investigating the impact of climate change and the increase in CO2 in the atmosphere on marine habitats and species.

The English name “gold coral” refers to the prevalence of the light yellow color that characterizes the colonies of polyps of Savalia Savaglia, until some time ago called “Savaglia savaglia”.

They are among the most beautiful and spectacular creatures of the underwater world. With their colorful branches, waving so much as to suggest the name of "sea fans", they were anciently mistaken for plants, before being recognized as animal organisms, whose classification has been the subject of revision, based on the results of more recent molecular studies.

Copyright © 2026 Mare.it. All rights reserved.

The texts published on this site have not been generated by AI (Artificial Intelligence).