In the Mediterranean, the Portuguese Man O’ War (Physalia physalis) is still considered an "alien."

It took ten years, from its first appearance in the eastern Mediterranean, for it to arrive in the Italian sea, in Lampedusa. And since then, it was 2013, it took another twelve years to travel up the Adriatic, until it reached Croatia, where an adult male specimen was just found in the northernmost point among those where the Silvery or Spotted Puffer Fish (Lagocephalus sceleratus) had been reported so far. Another Lessep

sian alien that does not stop its advance to conquer the Mare Nostrum and that is not at all welcome, considering that it is a toxic species, that does not bring any benefit to the ecosystem, on the contrary.

Like the other approximately two hundred species of puffer fish, the “silver” one is also native to the Pacific and Indian oceans, where it lives in coral reefs and along the coasts. And the Lagocephalus sceleratus is linked to the others by the presence of a poisonous substance, tetrodotoxin, from which the name of the Tetraodontidae family comes, which is one hundred times more toxic than cyanide. In fact, it has caused numerous cases of poisoning and even death in the eastern Mediterranean where the inexorable expansion of the puffer, arriving from the Suez Canal, began.

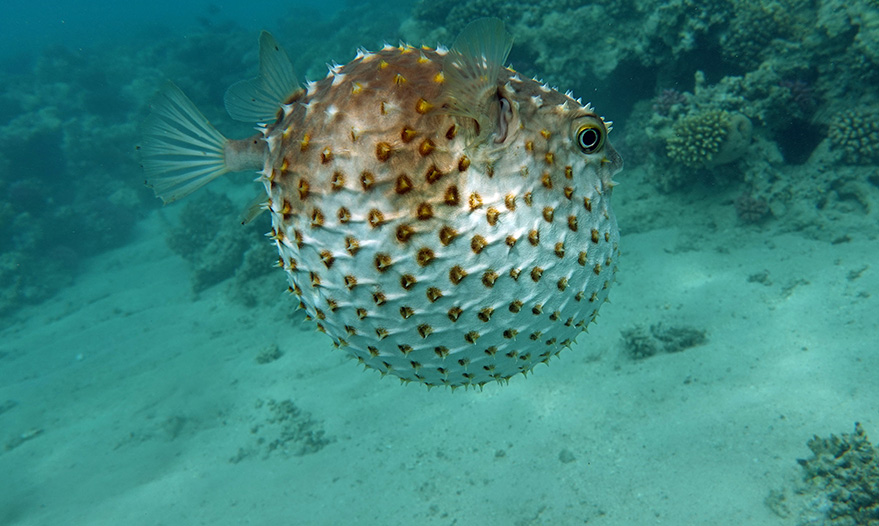

This is an animal that is decidedly armored against any potential predator: a bony fish, with a large head and large eyes, a single dorsal fin, without scales, but with spines on the belly and back, which remain close to the body and are almost unnoticeable when the animal is calm. They rise, ready to cause damage to the opponent, only when the fish swells, with the defensive mode that most identifies members of the entire family: it takes in sea water from its mouth, which it pushes into a diverticulum up to a closed bag in the stomach. When it swells, the spines also come out, making it indigestible and dangerous even for sharks.

The toxic substance is present in the innards, but makes every part of the body poisonous, even after normal cooking. Therefore, the puffer is also dangerous for humans both in contact with any part of the body and if it is ingested, with the exception of a cooking technique developed to make it edible and used by the Japanese, who are the only ones to eat it and also consider it a gastronomic delicacy. In Italy, the consumption of puffer fish has been expressly prohibited since 1992 and fishermen are required, in the event of accidental capture, to immediately isolate it from the rest of the catch.

Another dangerous part of the puffer fish is its mouth. In order to feed on pieces of coral, crustaceans and mollusks, it has very strong teeth that allow it to break and crush shells, shells and coral structures. Therefore, if it thinks it is being attacked, it can also bite humans, causing irreparable damage to their limbs. However, among the puffer fish's prey there are also worms and sponges and in order to extract them from the sand, it causes a strong jet of water that facilitates its capture.

The silver or spotted puffer fish like the one caught in the upper Adriatic, in particular, has an oblong body and is silver in color with black spots on the back.

In order to monitor its expansion, the collaboration of fishermen is essential. In case of capture, they are invited to photograph the specimens and promptly report it to Ispra.

In any case, anyone who spots a puffer fish can report it to

Si era ancora nel dopoguerra, quando lo scarico delle acque di sentina di qualche nave proveniente dall’Oceano Atlantico affidò al Mediterraneo una nuova specie di granchio che nessuno conosceva. E di cui ancora a lungo si sarebbe ignorata la presenza nella laguna di Grado, in Alto Adriatico, dove era comparso per la prima volta nel lontano 1949. Nulla lasciava presagire allora e neppure nei decenni seguenti che il Granchio blu, nome scientifico Callinectes sapidus, settant’anni dopo si sarebbe rivelato un vero e proprio flagello, capace di stravolgere interi ecosistemi e di annientare una delle specie animali di cui è predatore, la preziosa vongola dalla quale dipende l’economia di tante aree della costa adriatica.

Dopo tanti anni di silenziosa, anonima presenza nelle lagune dell’Italia nord-orientale, riconosciuto solo nel 1993 ma ancora apparentemente innocuo, il granchio nuotatore, come pure viene chiamato, ha iniziato a moltiplicarsi in modo esponenziale a partire dal 2010, dando inizio a una diffusione velocissima, che lo vede ora stanziale in quasi ogni parte d’Italia, anche se i danni maggiori li sta facendo nell’Adriatico tra Friuli, Veneto ed Emilia-Romagna. Una proliferazione incontrollabile da ricondurre all’innalzamento delle temperature a terra e a mare, che hanno portato al livello massimo la prolificità della specie. Originaria dell’Oceano Atlantico occidentale, dove è presente dalla costa statunitense fino all’Argentina, e in particolare nel Golfo del Messico. Orami insediata, tuttavia, oltre che nel Mediterraneo, anche nel Mar Baltico, nel Mar Nero, nel Mare del Nord e nel Mar del Giappone. Un areale immenso, che si incrementa a vista d’occhio.

Crostaceo della famiglia Portunidae, il granchio blu si identifica anche nel nome con la sua colorazione più vivace e appariscente, il blu di alcune parti delle zampe e delle chele, nelle sole parti laterali per tutti gli individui e per i maschi anche nelle punte, che invece nelle femmine sono di uno squillante rosso aranciato. Altro elemento di dimorfismo sessuale è la forma dell’addome: nel maschio somiglia a una T, nelle femmine adulte è ovale rotondeggiante e triangolare nelle giovani. Come tutti decapodi, anche il granchio blu ha cinque paia di zampe di cui l’ultimo paio posto anteriormente, più lungo degli altri quattro, è trasformato in chele.

Il corpo del maschio raggiunge i venticinque centimetri di larghezza, quello della femmina, più piccolo, i venti. E la larghezza è il doppio della lunghezza. Il carapace presenta sia nella parte anteriore che in quella laterale nove paia di denti, di cui il più posteriore è allungato a formare una spina. Due denti triangolari sono pure sulla fronte.

Prolifico e capace di vivere nelle più varie condizioni

Il granchio blu vive in media tre o quattro anni, al massimo può raggiungere gli otto. Ha una grande capacità di adattamento sia alle temperature - dai 5 ai 35 gradi - sia al grado di salinità delle acque: da quelle più dolci degli estuari dei fiumi, a quelle più saline delle lagune e del mare, fino ad acque fortemente salate. I maschi preferiscono acque meno salate, le femmine più salate come i neonati. I granchi popolano habitat sabbiosi e fangosi, ma nella fase giovanile crescono al sicuro nelle praterie di fanerogame marine. La capacità di adattamento si riscontra anche nell’alimentazione, visto che è un animale onnivoro, che si nutre di alghe, di crostacei, anellidi, piccoli pesci e perfino di insetti. Ma apprezza particolarmente i bivalvi, tra cui cozze, ostriche e vongole. Nei casi di forte affollamento e di riduzione di altre prede, è normale il cannibalismo di esemplari adulti e più grandi rispetto ai piccoli.

La specie è straordinariamente prolifica. Anche se le femmine si accoppiano solo una volta nella vita, dopo l’ultima muta, mentre i maschi più volte. Ogni femmina depone dalle settecentomila agli otto milioni di uova e lo fa spostandosi in tratti di mare con maggior livello di salinità, perché è la condizione ideale per le larve che nascono dopo il periodo di incubazione della durata tra i quattordici e i diciassette giorni.

La grande capacità riproduttiva del granchio blu, unitamente alla varietà di condizioni in cui gli è possibile vivere anche nel Mediterraneo, hanno fatto sì che questo granchio alieno riuscisse a insediarsi stabilmente in aree costiere sempre più ampie e con popolazioni sempre più numerose, che i predatori naturali – pesci, tartarughe marine e uccelli – non riescono a contenere. E vale anche per il predatore principale, ovvero l’uomo, tanto che ormai gli eserti concordano sull’impossibilità di eradicare ormai il granchio blu dal nostro mare.

Eppure, si tratta di una specie che rappresenta un problema sempre più serio per l’impatto estremamente distruttivo che ha sull’ambiente. Dove si moltiplica il granchio arriva il deserto, vista la voracità con cui annienta le specie di cui si nutre, colpendo in particolare gli allevamenti di vongole in Adriatico. Negli ultimi anni, i granchi hanno determinato una riduzione di oltre il 70 per cento della produzione di vongole nel Delta del Po, infliggendo un colpo durissimo all’intero comparto economico e all’occupazione che vi ruota intorno.

Per cercare di contrastare l’emergenza granchio blu sono stati previsti investimenti specifici, mirati a sostenere gli allevatori/pescatori di vongole e a finanziare ricerche sui granchi e azioni specifiche di contrasto. Il tentativo di contenere la moltiplicazione dei crostacei, trasformando essi stessi in un prodotto commerciale per il consumo umano, non ha avuto i risultati sperati. Se, infatti, il granchio è considerato una leccornia nei Paesi atlantici di cui è originario, in Italia e in Europa non ha avuto finora altrettanto successo. Per cui la perdita delle produzioni di vongole non è stata compensata dalla commercializzazione dei granchi, come si auspicava.

Tra le ipotesi di contrasto alle quali si continua a lavorare, vi è la ricerca di predatori naturali in grado di contenere le popolazioni in crescita. E le notizie più recenti segnalano con interesse la possibilità che il polpo comune (Octopus vulgaris) possa diventare un efficace nemico, in grado di ripristinare un minimo di equilibrio lì dove il crostaceo blu lo ha compromesso. Riuscirà a portare a buon fine l’impresa, il campione dai lunghi tentacoli?

A great work destined to revolutionize navigation, international trade and the world economy.

All this was well known to those who, investing considerable resources, wanted to build the Suez Canal, inaugurated in 1869. Not as much attention and consideration had probably been reserved for the environmental changes that that intervention could have brought about in the short and, even more so, in the long term. Certainly, Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, at the head of the French company that had built the canal connecting the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, would never have imagined that so many decades later, in 2010, his surname would give rise to an adjective, “Lessepsian”, coined by the great Romanian zoologist Francis Dov Por. An adjective that has since then been used to define all organisms, mostly animals, but also plants, that have moved from the tropical environment of the Red Sea and also the Indian and Pacific Oceans to the Mediterranean and have settled there permanently.

They are the vast majority of the so-called “alien” organisms, since the number of species that arrived from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar is much lower. Moreover, animals and plants that followed the reverse path from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea are defined as “antilessepsians”, but in rather small numbers.

The first aliens were passively introduced into the new Mediterranean area with the bilge water of ships or attached to the keels. Only later did the actual migration begin, favored over time by some changes linked to the long-term effects of the environmental impact of the canal and related works. At the beginning, in fact, the movement of species from the Red Sea was blocked both by the different temperatures of the Mediterranean and by the very high salinity of the Bitter Lakes, an integral part of the canal. In those lakes, the species that ended up there did not survive. It was, therefore, an extremely effective natural barrier. But then the external connection determined the introduction of fresh water into those basins, which progressively reduced the initial salinity by half, making the Bitter Lakes a viable connection also for the native species of the Red Sea, as well as for ships. The construction of the second Aswan dam in 1971 and the restyling with the expansion of the canal in 2015 created other conditions favorable to migration.

Between the end of the 19th century and the end of the 20th century, it was observed that most alien species, all of tropical origin, once they entered the Mediterranean, remained in its southernmost and easternmost part, finding habitats more compatible with those of origin. The rise in sea temperature, which has accelerated in the last thirty years, with an increase of about one degree, has made an expansion towards the west possible. And, in addition, that towards the north has been added, which is also affecting native species.

The story of Halophila stipulacea is exemplary: the tropical marine plant was first spotted in the Mediterranean in 1894. Since then, it had remained in the eastern part of the basin for a long time, before starting to spread westward, until it appeared in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where it reached France, and in the Adriatic. A study by the University of Salento, published in 2023 in the scientific journal “Mediterranean Marine Science”, revealed that the plant has formed large meadows off the coast of Salento, so much so that researchers have launched an appeal to assist in the monitoring activities necessary to verify the transformations in the marine environment, induced by such a massive presence of the alien.

The same phenomenon has affected, or rather is still affecting, many of the animal species from the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Among the many, the dark rabbitfish (Siganus luridus), which is very widespread in the eastern Mediterranean, where its strong environmental impact has already been experienced. In fact, as a herbivore that feeds on brown algae, it has created a lot of damage where its presence is massive. In Italy it was sighted in 2003 for the first time and since then, although sporadic, other sightings have followed. The same can be said for the striped rabbitfish (Siganus rivulatus), which appeared in Italian seas for the first time in 2015.

Page 1 of 2

Copyright © 2026 Mare.it. All rights reserved.

The texts published on this site have not been generated by AI (Artificial Intelligence).